Giotto Bizzarrini, the genius of aerodynamics

His eldest son Giuseppe, mechanical engineer as well who worked for Auto Delta, recalls the main successes and the personality of one of the most acclamated genius of the automobile history of all time

Test driver, designer, builder. Giotto Bizzarrini was one of the most creative, brilliant and innovative minds of the motoring world. A free spirit guided by a passion for experimentation, since the 1950s he has made a fundamental contribution to the development of the automobile thanks also to the formidable insights that his enormous talent has been able to provide. Each time he has set new, dazzling standards of performance and each time he has given the world absolute masterpieces. Masterpieces that today are contested by collectors with tens of millions of euros. He was born on June 6 1926 in Livorno, he graduated from the University of Pisa and joined Alfa Romeo a year later, in 1954. We retrace the rest of his intense professional history, in the main salient features, together with his eldest son Giuseppe, 68 years old, the eldest of four children and a mechanical engineer as per family tradition. “My grandfather was a civil engineer, though: an expert in hydraulics and maritime works”, he explains. After four years in Auto Delta he collaborated with Abarth, Fiat, Zagato and Alfa Romeo for the ES30 (SZ). He specialized in the field of composite materials and in 1981 he designed the first full carbon fiber frame of the Biscione and the Formula 1. And, of course, he did some collaborations with his father. While his mother, Mrs. Rosanna, who passed away in November 2020, worked with Giotto in the Seventies, creating the bodywork of many projects realized after the closure of Bizzarrini Livorno. But let’s start from the beginning.

Does the Topolino (Fiat 500) that your father modified as soon as he graduated by making it aerodynamic still exist?

“Yes, it is in a collection that if I remember correctly is in Brescia. It was built in the workshop of Mr. Pasqualetti of Pisa, who was behind the engineering faculty”.

That saounds like a sacred place for future mechanical engineers.

“Well, I think my dad spent more time there than studying (laughs). He had a passion for aerodynamics and preferred to experiment rather than sit at the desk. There are some photos of the Topolino with my great-grandmother and me at the wheel: I must have been three years old, more or less”.

Of the two sons, are you the one who worked the most with Giotto?

“My brother Pietro, born in 1956, actyally worked together with him more than me. For a while we also worked all together: that was in the Seventies, for the AMX3 of American Motors”.

What was it like working with your father?

“Isn’t there a back-up question?” (Smiles).

Did you move to Milan as soon as you finished your studies?

“Yes, I still worked with my father in the workshop during the first year of engineering, but I soon realized that this way I was unable to study. I moved to my grandfather’s and after graduation I went to work at Auto Delta with engineer Chiti”.

Carlo Chiti was Tuscan as well.

“They were friends with my father. When we lived in Milan (from 1954 to 1957, the years when Giotto Bizzarrini worked in Alfa Romeo, ed.), we lived in Piazzale Lotto in the same building. They likely met in Alfa, however they also worked together in Ferrari, where my father applied and I think he proposed the engineer Chiti, who arrived shortly after. At Alfa Romeo my father was in the Experience Department, directed by engineer Rudolf Hruska, and I believe that it was he himself that proposed my father to Ferrari because on the one hand my father had solved some problems of breakages on the Giulietta chassis and on the other hand the engineer Hruska realized that he was not exactly suited to working in a team, as they say now (laughs). He then told him to apply and my father was hired as a test driver of the production cars in place of the engineer Sighinolfi, who had passed away shortly before”.

Your father worked on the most admired Ferraris of all time… Testa Rossa, 250 GT Ellena, 250 Spider California, 250 SWB, 250 GTO… an impressive sequence.

“Those cars were Ferrari projects in which he did his part of testing and tuning, while for the 250 GTO he created the whole project. When the Commendatore told my father to develop a completely new car because he feared the release of the Jaguar E-Type, in 1961, he gave him the indication to transform the company car he was equipped with, which was the Ferrari 250 GT Boano. At that point my father put into practice the aerodynamic ideas that he had developed during the tests: all the cars “floated” at a certain speed, the steering became lighter and there used to be a loss of stability. So he had guessed that the shape must be the opposite of what most of the cars of that kind had, that is a rather high and rounded nose, massive, with a very thin tail that was lowered. A kind of wedge had to be made. He cut the frame of the Boano behind the seat, shortened the wheelbase to bring both the driver’s seat and the engine closer to the rear axle, moved the engine back further to increase the weight on the rear axle, and began to build the bodywork by hand, beating the sheet metal and creating the shape that then became the very low nose of the 250 GTO with the front air intake. The radiator, however, did not cool down enough, therefore he opened those three vents above the nose that are Naca air intakes used in airplanes: they were used to power the radiator and at the same time to reduce the flow of air that passed over the car. My father knew them because he was fond of fighter aircrafts. He was also convinced that cars should not be designed by stylists because aerodynamics should have led to the conception of an optimal car like an airplane …So cars at some point should have been all the same, only aerodynamic”. (Laughs)

Center of gravity and aerodynamics were his main themes, in fact.

“Yes, in this case the center of gravity moved the mass to a central position to have less inertia, then the car was still very low and the rear was very high, even if not perfectly truncated. The tail is particular, it has a fairly indefinite rounded shape: I never understood why he did it this way and unfortunately I can’t ask him anymore because it is impossible for him to remember details that are so distant in time”.

The tail recalls the one of the 250 SWB.

“That the components are those of the 250 SWB is evident, but the rear window is mounted much higher and much more inclined, so much so that from the cockpit you probably can’t see anything through the rear-view mirror. In addition, the two fenders protrude from the rear window area and create two sort of fins that perhaps have a stabilizing function. Then, having shifted a lot of weight to the rear, my father mounted rear tires larger than the front tires on this car for the first time, in agreement with Pirelli. The result, when he went to test it, was that the car, nicknamed “the Duck” due to the low and thin front which, with the three air intakes above it recalled the beak of a duck, was extremely stable. By force of circumstances it was not tested in the wind tunnel because they began to build it in June and it was already tested in August in the Modena circuit, then in Monza at the Grand Prix tests. However, during those tests the car had a very high top speed in proportion to the power used: it exceeded 300 km / h. A problem that emerged showed that it had a much higher transverse acceleration than the cars of the period, because the oil warning light came on in curves as the oil in the sump was spinning. It is possible that due to the shape of the rear, a vacuum bubble was created that drew the air from below, triggering a kind of ground effect”.

That was a great success.

“La Papera” (“The Duck”) lowered the track record by 7 seconds, a monstrous result that is unthinkable today. Then it was abandoned and dismantled almost immediately and, shortly after, there was that strange mutiny of the engineers in Ferrari, the so-called “Rivolta di Palazzo”, (“Palace Revolt”). My father told me that he sided with the others because, let’s face it, it’s not like he was a great politician. Ferrari convocated him and was very angry at the fact that he was leaving. “Take your Duck and bring it away!”, he shouted. He was upset, he hoped he would stay”.

But Giotto had no reasons against Ferrari, quite the contrary.

“Indeed. But I never knew the details of this story. I don’t know anything about that period also because with my mother and my brother, for health reasons, we no longer lived in Maranello but had moved to my grandparents, near Livorno. In 1960 I was in lockdown: at that time it was not generalized and it was not called that but in fact I was locked up at home for a year due to the consequences of the Asian flu. I started school, got sick and after Christmas we moved to the sea on the advice of the doctor. This too, that is the desire to reunite with the family, may have influenced my father’s decision to leave Modena. Maybe to open a business in Livorno”.

The engineers then formed the ATS, while Giotto dedicated himself to another masterpiece, the “Breadvan”, for Count Volpi di Misurata.

“He built the car with a workshop in Modena, this time on the basis of the Ferrari 250 GTO developed by engineer Mauro Forghieri. And there weren’t even any drawings, because it had been built in the workshop and only tested. Engineer Forghieri substantially maintained the pattern of the nose and redesigned the rear part, which returned to the previous forms, lower and more rounded, perhaps also because the shape of the Duck was objectively ugly. The result was that when they went to test, the car had lost stability and speed”.

But you glossed over when I asked you what it was like to work with your father.

“Ehm, working with my father… He was the boss, full stop (laughs). In the “Duck” team this approach worked well as the mechanics did what he said, but elsewhere it wasn’t always that simple”.

And how did Giotto live this paternity?

“He said that the 250 GTO was not his work: he had done “The Duck” (laughs).

…That is the one that spun.

“Exactly”.

At Goodwood, England, at the annual event that commemorates the races of when the circuit was active, that is, from 1948 to 1966, it is all a triumph of Giotto Bizzarrini’s work. There are the most spectacular cars he has worked on, such as the 250 SWBs, and above all the 250 GTOs and the Breadvan, which are his work.

“If we look closely, the Breadvan is the obvious evolution of the “Duck”, because the muzzle is even more flattened, the beak holes are even more pronounced and larger, and the tail is perfectly truncated. So if you go to calculate the vehicle’s incidence axis, it is the maximum possible. In fact, at Le Mans it was much faster than the 250 GTO”.

It would be nice to take him, Giotto Bizzarrini, to the Goodwood Revival. The British public raves about his cars, even if they tear up the Aston Martins and E-Types.

“Even the Jaguar E-Type, which Ferrari feared before it came out, has an aerodynamic shape that, judged by today’s knowledge, is wrong. It’s a very aerodynamic model but with the effect of a supporting wing. It would be interesting to test the Breadvan in a wind tunnel on a 1:1 scale and examine its characteristics”.

Then, among the many professional challenges your father won, there was the Asa 1000 GT.

“The so called Ferrarina was an opportunity for him to transplant his business to Livorno. After leaving Ferrari he had opened his own workshop to provide consultancy, which was called Autostar: the first order was the development of the Asa 1000 GT”.

Of course your father has always been a daredevil. He went in and out of companies without worrying about the risk of being unemployed.

“That’s true. He had no sense of danger”.

How was this discontinuity experienced in the family?

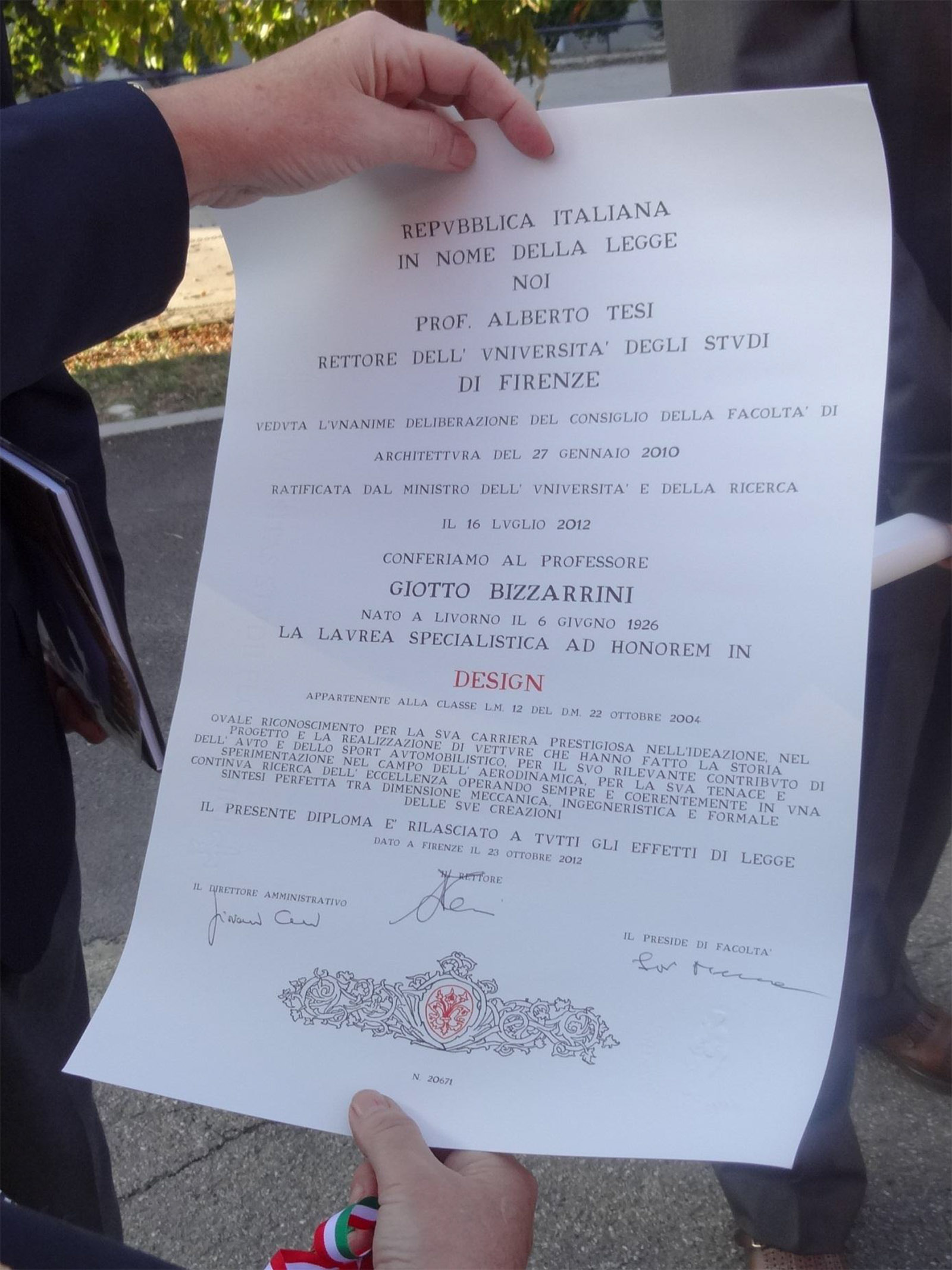

“We did not really perceive it. We felt it later, in 1969, when the Bizzarrini was closed. He has founded three companies: Autostar, which was closed and transferred to Prototipi Bizzarrini, and Bizzarrini Livorno, which went bankrupt. Since then my father has continued to do several projects, many of which have not materialized. Until, in the mid-seventies, he entered the university thanks to Professor Dino Dini of Pisa, who called him, and then he was given a course in Florence, where the engineering faculty had meanwhile developed. However, he always continued to design: for example the Picchio, started in 1989. One thing that no one knows is that in the early Seventies he consulted for the Dalle Molle Foundation, owners of Cynar (a famous Italian spirit, ed.), as they wanted to produce an electric car”.

Indeed Giotto Bizzarrini has in many cases given the spark for projects continued by others.

“He has developed many ideas and projects ahead of their time. In the Nineties he thought of a hybrid car – before Toyota came out with the Corolla – using a diesel engine, which is the internal combustion engine that gives the most efficiency. The car was equipped with reversible electric motors, which during braking returned energy that was stored in a group of super capacitors: these stored the electricity that was returned to the engine, transforming the car from two to 4-wheel drive when exiting the curves”.

A great inventor. According to many, he wasn’t interested in getting promoted, though.

“That’s it. The commercial aspect has always been the weak side of him”.

Does Giotto’s wind tunnel still exist?

“Yes, it is at the University of Florence”.

Did you and her father discuss professional matters?

“No, zero. Also because I settled down away”.

Giotto’s personality has always been charismatic. Several loyalists who have worked with him have also left jobs to follow him in his projects.

“Yes, it’s true. Mauro Prampolini has always had a sort of veneration for him. Also Stefano Volpi, a welder named Pacini and the mechanic Sancasciani have always remained fond of him”.

He was a free spirit. In your opinion, was there anyone with whom he would have liked to work together?

“No, he didn’t get along with anyone”.

Was he precise, a fussy eater?

“In some respects yes, in others no. In my opinion he was not even too attentive to detail. He had a conceptual design approach. It could still work in the 1950s but when you then went to put a car on the road to participate in the 24 Hours of Le Mans you needed the concept but you also need the detail because if you don’t tighten a clamp well and a tube comes off and you lose the oil in bottom you’ll never get to the end”.

How did he experience the interest on the part of the newspapers, which still continues today with frequent articles in every part of the globe?

“In my opinion he was not interested in that much”.

He wasn’t vain at all, then.

“No, because he was more into what he had in mind to do than what he had already done”.

Every now and then someone comes up announcing the rebirth of the Bizzarrini brand. For the most part they are bogus throws, they only demonstrate the great admiration that still exists for your father. Now, however, while a Belgian designer has remade a model of the Breadvan in a modern key, it seems that someone else is getting serious: the Pegasus company set up by a former manager of Aston Martin. Did you sell the brand in 1969?

“We sold it later, at the end of the nineties. Then the Bizzarrini brand passed from hand to hand. But in fact, no one has been able to really build so far, apart from another prototype created years ago, which remained so. Now this Kuwaiti company based in London is taking the initiative, but to produce cars, very strong investments are required, including making handicrafts, one-offs or very limited editions. While my father’s projects had a logic in the development of the automobile. In fact, the study of modern aerodynamics in racing cars began with “The Duck” and ended when Colin Chapman discovered the ground effect: after that there were only developments and applications”.

Ferruccio Lamborghini had asked your father for a V12 for the brand’s first GTs, but there was some discussion at the time of delivery: did he get paid, at least?

“Yes, but in a certain sense this story defines the character of my father, who had accepted a horse contract. Can it be? The concept was “the more horsepower the engine makes, the more I pay you”. There was already something questionable here. My father designed and built it in Modena and then took it to the test bench at the Lamborghini factory in Cento, near Ferrara. The V12, which followed the pattern of the Ferrari engines, was a 3-liter, and at the first test it gave a power of 360 horsepower, therefore much higher than expected. At that point Ferruccio Lamborghini calculated how much he had to pay: at least there were 60 more horses, which meant a considerable addition in terms of compensation. “But how can I mount such an engine on a road car?”, he replied to my father, who got immediately angry. But it was an engine with which the brand went on for a lifetime and also my father could have worked on it for years”.

Emotionally did he use to attach himself to his creations, did he want to possess them?

“I wish he had wanted to. The “Duck” would have been invaluable”. (Smiles amused).

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED