Pietro Camardella: “So I designed my Ferraris”

Author of the aesthetics of the Ferrari 456 GTM and of the spectacular Mythos, he also worked on the F40 and designed the restyling of the Testarossa

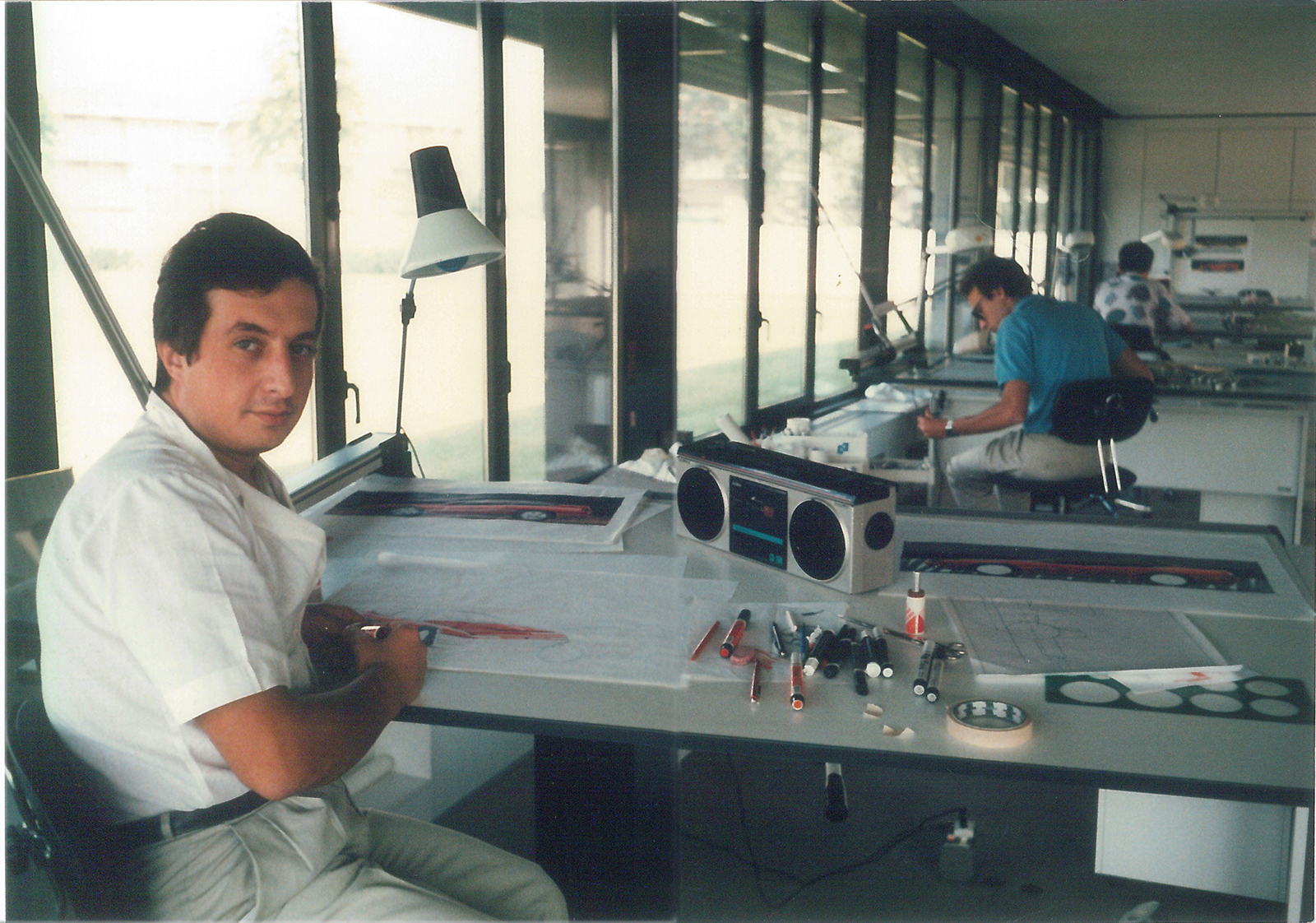

“How can you expect that in Turin they need a guy from the South to design cars?!” I used to hear this sentence a lot when I was a young man”, underlines Pietro Camardella, designer of several Ferraris of which one, the 456 GTM, remained in production for 11 years, and another, the Mythos show-car, that won the prestigious Car Award of Auto & Design. Born in Salerno, 64, he joined the creative Pininfarina team after being selected by the great Aldo Brovarone. After five years there he started his own business as a freelancer and later worked in Lancia. Now he is in the Fiat Research Department that he joined in 1998. The beginning of his career has not been simple, though: “Many people used to remind me of that unpleasant concept of being meridional, although I was already working in an architecture company”, the designer recalls. “I never got a degree but I studied architecture. After the 1980 earthquake I lost my job, therefore I started to work as an accountant in a company in my home town. It turned out that the owner had a cousin who worked in Pininfarina, who positively judged the drawings that I was doing at the time and directed me to engineer Leonardo Fioravanti”. When fate is said. Thus began a series of interviews, then the internship and finally the assumption.

How many people used to work in the Pininfarina Style Office at the time?

“It might seem incredible but we never got to ten, the top was eight. The year of the F40 we were even less: one of us had resigned, another was in the army. The management decided that I would design the car, obviously under the supervision of Aldo Brovarone: it was considered a restyling, after all. There were the 400 + 100 chassis that were needed to obtain group B homologation, which Ferrari gave up. The choice was then to produce a racing car in a road version, in a limited series”.

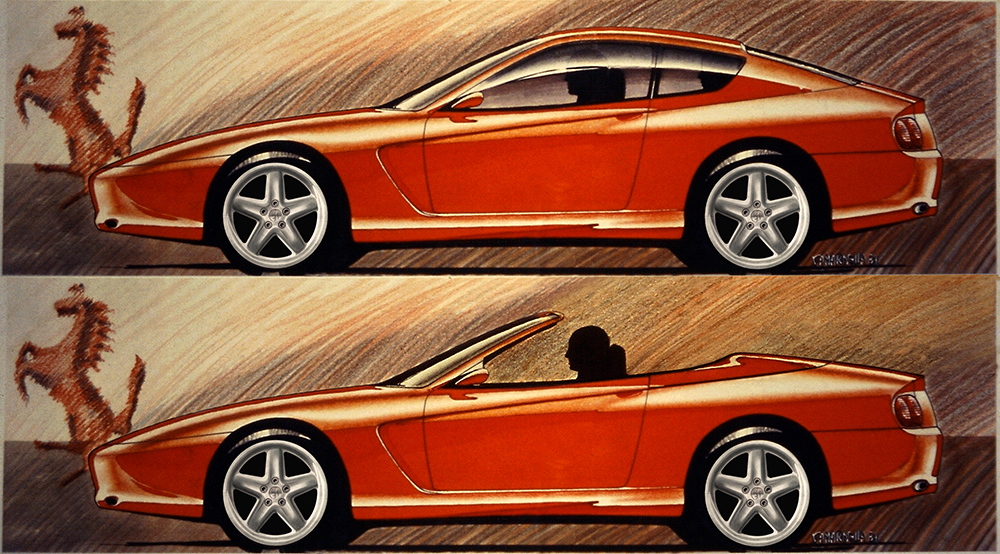

However, it was the 456 GTM, equipped with the traditional 12-cylinder V-front, that marked your debut in the temple of automotive style.

“That’s the first project I worked on inside the firm. A competition was launched within the Style Office and each of us designers prepared 2-3 proposals. In this case the mechanical base was of the Ferrari 412; I remember that I had considered the recovery of the Berlinetta setting, with the rear window that descends and fades into the tail, but at the time the three-volume fashion was winning. Later, in 1989, the competition to redesign the 2 + 2 was held again and my idea won, with the fast back tail although slightly inflected”.

What was the impact of Aldo Brovarone and what was it like working with him?

“Aldo Brovarone was a modest, old-fashioned guy. A gentleman of yesteryear with an all-Piedmontese attitude to work. I used to call him “the antichrist of design theory”, because he was a pure artist, his ideas sprang from him. He was the first person I ever met in Pininfarina, in November 1984. I didn’t know who he was, communication was poor at the time and his was not a famous name. He was kind, at times he seemed shy. He introduced himself apologizing for the executive with whom I actually had the appointment, and was vague about his role, he just called himself the senior in the Style Department. He emphasized his many years of “faithful service” and, in his elegant and militaristic language, he lit up when he spoke of the “president”. All these details immediately made me understand how much he loved the company. I started my internship in May 1985: from then until Aldo Brovarone’s retirement in 1988, I had a relationship with him based on professional esteem. Although we came from different generations, the “professional camaraderie” made us feel joyful together within the incomparable group that we were, something really never found again in my professional life. We only became truly friends when we met again many years later. In his discreet manner, he told me that it was time to speak to each other forgetting about the formal courtesy pronouns”.

You also worked on the retsyiling of Testarossa.

“Yes, it was an honor to put my hands to such great wonder. The task was given to me in 1987, I worked hard and, in the end, a good job came out, which maintained two years of sales. First of all, I retouched the side, increasing its power without the black band consisting of sill and front spoiler. I remodeled the front bumper, worked on the bonnet and got rid of the old grille. In the same year I also had the opportunity, with the New Mondial, to obtain a balance of volumes and proportions on a four-seater with a rear engine, combining sportiness and lighter tones. However, the project was suspended”.

What makes you nostalgic for those years and what would you have done without?

“Talking about Pininfarina, I give the company all the credit for having consolidated the best production system at the time, which gave the greatest creative freedom in the first phase. There were other ateliers, which I will not name, where employees had to learn the chief’s technique so that the hand was always traceable to him. Then, of course, in the development of a project there is always an inevitable compromise for construction needs. Another memorable factor of that period were the artisans, fabulous: in Pininfarina I called them the “multiplier” of the company. That is, if a designer was worth one, one by ten was equal to ten, but if he was worth ten it he became a hundred. Because the extraordinary ability of the workers to achieve made the ideas much stronger”.

Mythos, based on the Testarossa, is a superb concept car born in 1988 which actually became a one-off…

“Yes, even if this term was not used at the time. The car, born as a self promotion of the company, was a great success. When it was presented in the Tokyo Salon it immediately won the Golden Marker Trophy and they used to request it from all over the world. Diego della Valle obtained authorization to land with an helicopter in Cambiano (where Pininfarina HQ were and still are) to try it, also Michele Alboreto wanted to buy it. However, the company decided not to produce it, until at a certain point the Japanese collector Shiro Kosaka came forward and bought it for a fairytale amount as a one-off. It was so unique that the “full model” had to be redone in a hurry after the sale of the car in order to keep a trace of it because the previous one had been destroyed due to lack of space. And… guess what? The Japanese customer arrived, saw the model and got worried: “Didn’t you say that the car was unique?!”, he exclaimed. We then explained to him that he was only looking at a model, a piece of wood. However, the Mythos influenced the F50, my “last but not least” Ferrari. I refer to it with affection as “The Unfinished” since I left the company when it was still at the beginning of development. It was later overwhelmed by the whirlwind of “infinite decision-making changes”.

This interview was partially published in La Manovella magazine

© UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION FORBIDDEN